We’ve all heard the saying “trust your gut.” Many of us do this more often than we realize. Trusting your gut means looking inward, beyond the noisy chatter of thought, and toward that fuzzy space of perception–a mix of instinct, intuition, and emotion–that somehow holds the mysterious power to direct you toward the “right” decision.

Instinctive gut reactions are often situational. It’s about the here and now. And trusting your “inner voice” can at times help by preventing you from over-thinking something and over-complicating matters. But when it comes to trading, simply trusting your gut on a situational basis can lead you down a dangerous and potentially destructive path.

Given the extent to which we make gut decisions on a daily basis, why doesn’t it always work when trading or investing? The answer, though simple, may come off as a bit odd: trading can be a counterintuitive act, particularly when you find yourself suppressing your own “natural” impulses to avoid the threat of risk or the pain of loss during moments of extreme market volatility or lengthy corrections.

Market Speculation Creates Friction Between Long-Term Thinking and Short-Term Experience

Let’s start with the basic premise that when speculating, even for short-term trades, you need to see the big picture; you need to plan your trading strategy over a long-term horizon. Regardless of your trading style, you probably need to go well into the past (e.g. long-term trend evaluation, backtesting, past market patterns and behavior, etc.). You also need to think about the future in terms of implementing, evaluating and re-adjusting your strategy and risk.

And here’s the rub: long-term “thinking”–which covers a wide expanse of time in just a few moments of analytical thought–is very different from the real-time durational “experience” that investors face when implementing a long-term investment strategy. In short, long-term projections and short-term experience are qualitatively different factors that are not always compatible.

But in the realm of practical experience, volatility elicits a real sense of visceral uncertainty; plunging you into fear, doubt, and at times, panic; tempting you to make rash decisions regardless of your sound reasoning and long-term planning.

Traders Tend to Fixate on and Magnify Losses

According to a study involving a sample group of U.S. investors (conducted in 1979 by economists Daniel Kahneman and Amos Tversky)–a study that applies to “speculators” in general, whether traders or investors– its findings estimated that the pain of loss felt by investors was approximately two and a half times greater than positive responses to equivalent gains. Behavioral finance has a name for this bias: myopic loss aversion. “Myopic” meaning nearsighted or shortsighted: a tendency to fixate on short-term drawbacks at the expense of long-term “vision.”

The emotional impact of this bias can be significant. A loss of 10%, multiplying that figure by 2.5, would feel like a loss of 25%. If we take that even further, a loss of 25% would feel like a 62.5% loss! If the study’s participants comprise a micro-sample of investors across the globe, then we’d come to the general conclusion that investors’ emotional response to profit and loss is significantly rigged in favor of the negative and skewed toward the recent past.

So how does this play out in a real-life market speculation scenario? What happens when a well-thought-out investment plan goes up against the experience of short-term volatility or loss; one that elicits an instinctive “fight or flight” response? The consequences are generally unfavorable, yet common.

Turning Buy Low/Sell High Upside Down

The basic premise for any trading is quite simple in theory: buy low and sell high. No matter how well you analyzed a market, you can never be certain that your buy point was low enough, nor can you be certain that your stock will rise. You can’t predict the future. However, you can make a reasonable projection based on what you do know. Just bear in mind that projection is not the same as prediction.

Buying low and selling high may seem like a simple concept; start here, end there. It’s never that simple: the duration between buying and selling is rife with unknowns, most of which materialize as fluctuations; often unfavorable, and at times, quite volatile. To make matters worse, your perception of these factors are often shaped, or bent out of shape, by your own instinctive aversion to risk. The bottom line is that if you allow yourself to get drawn into the chain of momentary uncertainties that sometimes dominate this in-between space, you run the risk of inverting the very premise upon which all investing efforts are grounded: you may end up buying high and selling low.

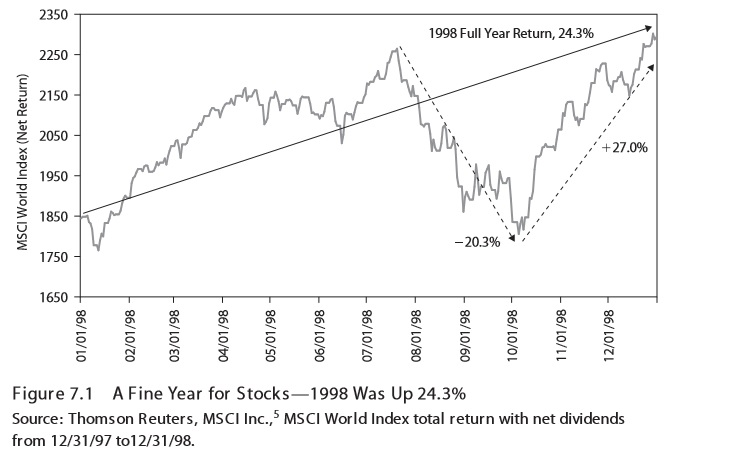

Take 1998, when the markets took a steep plunge and followed with a dramatic recovery.

1998 ended up being a great year for most of the world markets. But its volatility made the experience a remarkably trying endeavor. The previous year’s Asian financial crisis bred fears of financial contagion on a global scale. This crisis eventually led to Russia’s debt default. In the U.S., hedge fund Long Term Capital Management (LTCM), holding oversized bets on Russian bonds, collapsed. Investors feared that LCTM’s failure would crash the entire U.S. financial system. Hence, the sharp -20.3% correction.

Fueled by extreme sentiment, namely fear and panic, market downturns move much faster and sharper than upward advances. Steep plunges tend to trigger the “fight or flight” response in most investors, preventing them from approaching the larger fundamental outlook from a cooler, more rational perspective. This is generally true of most market corrections, and we can see how this dynamic took place in 1998.

A 20.3% drop is huge. But for most investors who had the tendency to magnify the emotional impact of losses, it probably felt closer to a 50.75% drop! But then, the market quickly found its footing and resumed its advance, ending the year with a 24.3% gain.

In hindsight, it’s easy for us to affirm that the right move was to stay the course. That’s because we have the privilege of seeing the outcome. But in every market scenario, you can only reach your destination by navigating through a fog of uncertainty.

The critical question is, should you navigate by plan, or whim; by reason, or sentiment; by strategy, or impulse?

Please be aware that the content of this blog is based upon the opinions and research of GFF Brokers and its staff and should not be treated as trade recommendations. There is a substantial risk of loss in trading futures, options and forex. Past performance is not necessarily indicative of future results.